The unhappy philanthropist

Why it might be wise to reassess how we view the committed major donor.

An unhappy philanthropist? That’s an oxymoron surely?

I think not, judging by how difficult some organisations find it to get repeat donations from major donors. Consider this. Browsing LinkedIn recently, I came across this post, from an American donor:

“I received an email that said I’m one of the three finalists for the APA Heritage Lifetime Achievement Award for my native American theatrical performances that I do through my non-profit organisation, Linking Rings Performing Arts Group. This was something I didn’t expect nor knew anything about and I feel honoured and humbled”.

Advertisement

Unusual?

Perhaps less so in America, but it would be very unusual here. I responded:

“Congratulations. You should feel honoured. I hope you feel pleased and special. I wish you well in getting through the final stage.”

In the UK we have conventions that recognise the best fundraisers and the best fundraising. But we have only a few awards for philanthropists. If we were true to our professed beliefs about donors, we would do more to recognise and honour them in the public domain.

Why shouldn’t philanthropists feel proud that their work is recognised by peers, fundraisers and the public? Could this be an example of actions not following words?

How did you feel?

I wondered if I was alone in feeling that, as a profession, we are being a little hypocritical? The awards ceremonies we put on for fundraisers are lavish to the extent that I would be embarrassed to see there many of the donors that I know. Then there’s the ‘Most influential 50…’ It seems we are good at hyping ourselves up. I have drunk my share of the champagne.

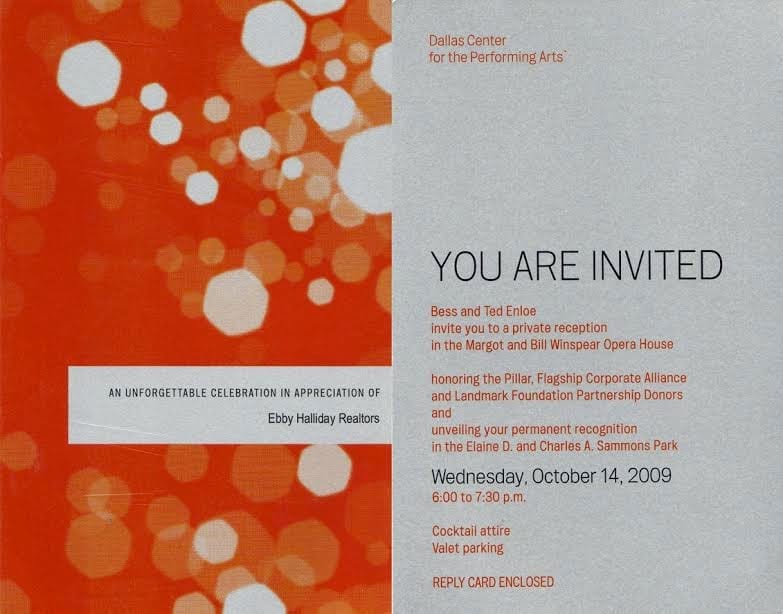

In America they put on dinners to honour individual donors. With individually made videos about their work, if they’re also volunteers, and the work they fund. They give the donor their moment of glory, of embarrassment, of pride, of joy.

Why don’t we?

Because we seem to think it’s somehow against our culture. If that’s so then I can’t quite see why fundraising awards would be part of our culture? I fear we neglect our donors. Not actively. I just don’t think we give enough, or any, thought to the feelings of donors, good and bad.

Can you explain this a bit?

Many fundraisers tacitly assume that philanthropists have all the tangible things they want in life and are using the ‘joy of giving’ to get spiritual satisfaction. I think we assume philanthropists are overindulged, or at least content. So, providing we are good at thanking, and reporting back on the impact of the gift, the donor will be happy.

I think we are wrong in thinking donors are so easily pleased

Go on.

OK. Then please read this.

“If you are a donor or philanthropist, when you struggle to give or when you have faced problems from being generous to whom do you share your heart’s cry with? Do you have a group of generous giving friends that will allow you to talk about the burdens and the blessings of practicing a life of generosity?”

How did that make you feel?

This knocked me out. It was written by a philanthropist I felt I knew. It went on:

“When you see your favourite charity continue to make arrogant mistakes or misappropriate funding, how do you go about addressing the many problems you face as a philanthropist? It’s important to have a network of support where you can share your heart, or even detox from toxic charitable experiences. There is nothing worse than feeling horrible from wanting to do well and make a positive difference in the world.”

How did that feel?

It was a light bulb moment, for me. I realised I needed to change my assumptions about fundraisers and philanthropists. That, for the philanthropist, with the opportunity comes responsibility, and with responsibility comes negative experiences and pain.

So…?

We should help. Where are we in the solution of the philanthropists’ problems? Without inappropriate probing, we need to find out more about how our donors and prospects feel about their relationship with you the fundraiser, the cause, the charity, the project, and the beneficiaries.

What does that mean in practice?

At the moment our solicitation plans are about how to get the donor to support the project. We don’t ask them:

– If the donor is confident we can deliver the project?

– Or if there is anything else that concerns them about the project?

– Whether they would prefer to consider a wholly different project?

– Is there anything that is concerning them about the charity?

– And what kind of recognition, appropriate to their gift level, would they like?

How do we do this?

The solicitation plan should be an engagement plan. It should identify if there is anything we can do to make this a truly joyful experience for the donor? And try to understand the holistic donor, not just keep pushing. They are partners, remember.

You will need to speak with others who know the donor, and can guide you to an understanding of the donor. In many cases this can only be done by the CEO, or the Chair of the Board.

How do we make donors partners?

It must come down to really understanding your donor and what he or she would appreciate. Individually. On a case-by-case basis. This will require a dialogue with the donor, and those that are close to them. It is really important that we give donors the opportunity of talking about the things two paragraphs above. If the donor is unhappy, it is imperative that we find out why. A lot of it will be down to how we recognise them.

• If they crave public recognition, put on a dinner or reception in in their honour. For ten people, or 200. If they are also a volunteer, create a short video of the work they have done, and the work they have funded.

• Get a tame journalist to write an article on their philanthropy.

• Produce a video of a celebrity/sports-person talking straight to camera talking to the donor. Show it to them with a small team. (If you can do that in person great. But much harder to do.) Still give them time with just the CEO.

• Name a building after them, or a room in a building. Take them on a site visit. (I know we do this.) Give them the opportunity of a private 1:1 with the CEO to explore their feelings. ( We don’t do that.)

• If they don’t want public recognition, invite them to a private sandwich lunch with the CEO, again to explore their feelings.

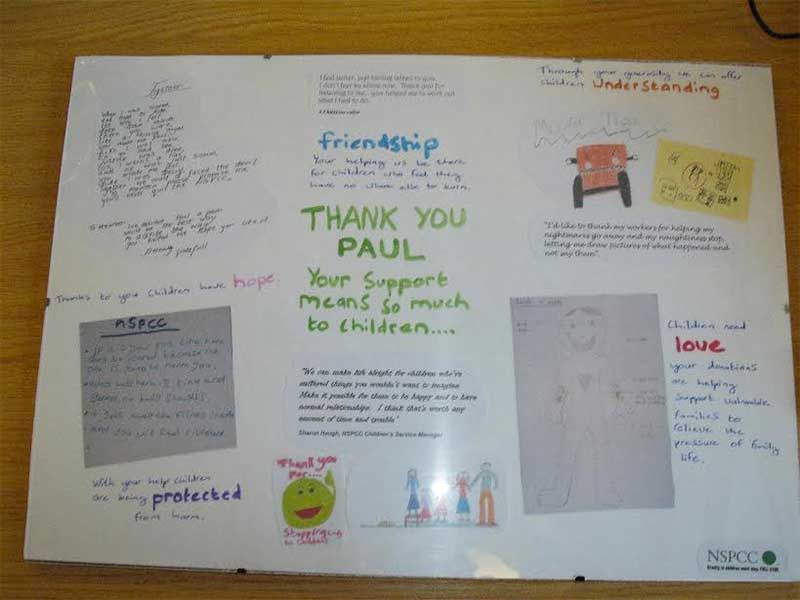

• Perhaps give them a small painting or poem written by a beneficiary, either in a group, or 1:1. Again, opportunity for 1:1 time with CEO.

• Or a montage, individually created. Show we are thinking of them, and open the door for them to talk to us. Again, individual meeting with the CEO.

I’m sure fundraisers reading this will have plenty of creative ideas for what they might do for their donors. That is more than thanking, recognising and reporting back, which many do very well, but a whole different level of personal engagement.

So…?

See your philanthropists as complete human beings, with the same needs for recognition, fears of doing the wrong thing, and disappointments that they might have made a mistake, as the rest of us.

Don’t allow any of your major donors to feel their voice has no opportunity to be heard, or their giving to be under-recognised. It’s all down to the complete donor experience.

Giles Pegram joined the NSPCC as appeals director and subsequently set up the highly successful 1984 Centenary Appeal, which raised £15m, a record at the time in the UK. Additionally, through adopting a donor-centric approach to fundraising, he grew the NSPCC’s income from donors and supporters from £3m pa to £145m pa (of which £85m came from regular givers) whilst the ground-breaking FULL STOP Appeal raised £274m to kick start the Society’s campaign to end cruelty to children. Giles continued as Appeals Director until 2010. He is now a freelance consultant. Giles was awarded the CBE in 2011.

© Giles Pegram CBE 2015. With thanks to Dr Gray Keller.